At the Engineering Design Celebration, students presented their prototypes and designs to industry and clinical sponsors

When asked about the challenges their team faced while discussing possible approaches for their senior design project, University of Delaware senior Michael Trainor put it simply: “The ideas are easy — making it actually happen is the hard part.”

This challenge of turning ideas into reality is at the core of what it means to be an engineer, and for students at UD’s College of Engineering, senior year is when students bring together the skills and knowledge gained during their studies to face that challenge head on.

These creative ideas-turned-prototypes were on full display at December’s Fall Engineering Design Celebration, an annual half-day conference at Clayton Hall that showcases and celebrates the work of UD’s talented Hengineers to alumni, UD community members, and industry and clinical sponsors.

Building engineers

Founded in 1999, the Interdisciplinary Senior Engineering Design Program is the combined capstone course that enrolls all seniors in the departments of Mechanical Engineering and Biomedical Engineering. This year’s showcase featured the work of 47 student teams, with 133 mechanical engineering students, 64 biomedical engineering students and four students from the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering.

Jennifer Buckley, associate professor in mechanical engineering, said that the portfolio of projects available to students in this program are very product-centered, with seniors working primarily on physical prototypes for more than 30 different industry and clinical sponsors, which this year included Keurig Dr Pepper, Agilent Technologies, Siemens Healthcare, W.L. Gore and the University of Cape Town.

“Senior design projects give students the valuable experience of practicing problem-solving and critical thinking, in an interdisciplinary team-based, time-bound, hands-on setting,” said Ashutosh Khandha, assistant professor in biomedical engineering. “This experience has a direct impact in showcasing engineering skills when students apply for jobs or internships.”

Tracy Shickel is UD’s associate vice president of corporate engagement.

“We’re very fortunate to have significant collaboration from external businesses and corporations that see the value in partnering with our students on senior design, and we get tremendous feedback from companies on the caliber of talent and the sophistication of students working on some of these projects,” Shickel said.

Also on display at the conference were projects from mechanical engineering juniors taking Machine Design, a two-semester course sequence that this year featured manufacturing and automation challenges from Norwalt Design and Omega Design. During the showcase, 15 teams of students, who had been working together in groups of 9-10 individuals, presented the mid-point results of their work toward designing, manufacturing and validating an automated packaging system for filling, capping and stacking pill bottles.

“Our junior year design experience provides an important stepping stone between earlier, highly structured design projects in our curriculum and the much more open-ended, sponsor-driven Senior Engineering Design experience,” said Adam Wickenheiser, associate professor in mechanical engineering. “Students must build upon skills they’ve developed in their previous courses as well as teach themselves and each other new techniques needed to succeed at these more complex projects. These students then go into their senior year excited and ready to hit the ground running.”

There were also presentations from students in the “Introduction to Industrial Design” technical elective, projects and pitches from local high school students in COE’s Engineering Education Ecosystem (E3) program and the wooden bike frame challenge by mechanical engineering sophomores in “Statics.”

Putting all the pieces together

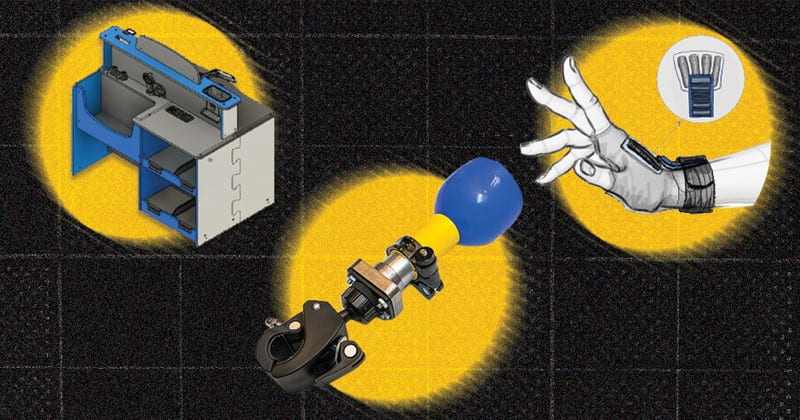

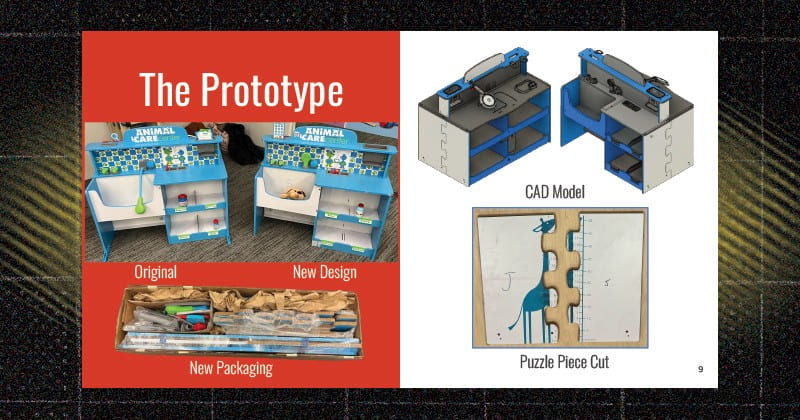

Mechanical engineering seniors Bethany Newton, Sarah Bartlett, Dani Moore and Zoe Smith took on Melissa & Doug Toys’ challenge to tweak an already successful product in a way that could reduce packaging and shipping costs for the design and manufacturing company.

Their job wasn’t to redesign the product, but rather balance competing demands to save on shipping and packaging mainly by reducing size, but not reducing the durability and stability of the popular easy-to-assemble play sets that include a modern play kitchen and even a veterinary clinic.

From left to right, Bethany Newton, Sarah Bartlett, Dani Moore and Zoe Smith worked with Melissa & Doug’s Rachel Belter (middle) on a project sponsored by the company to tweak an already successful product in a way that could reduce packaging and shipping costs.

For Moore, who is also minoring in math and integrated design, the project blended all the reasons she decided to pursue a career in mechanical engineering, especially the hands-on nature of a redesign.

“I figured we’d be doing a lot of designing and iterations of that design — that would be where our creative spark goes,” she said. How do you redesign something to be a much smaller size, cut in half even, without taking anything away?

Moore said they considered how they could cut it in half to make it more playful, and decided to look at it as a puzzle. By assembling the structure in smaller puzzle pieces, they were able to maintain the structural integrity of the design but also reduce the volume of the packaging.

“It was like a big, 3D jigsaw puzzle,” said Buckley, the team’s faculty adviser. “This is a real project that’s going to have real economic implications.”

While the focus of reducing the volume in packaging can save the company on shipping costs, the reductions also deliver some sustainability benefits by allowing more units to fit in tighter packaging with less waste as the product is shipped from overseas manufacturing sites to the United States.

By assembling the structure in smaller pieces, team 120 were able to maintain the structural integrity of the design but also reduce the volume of the packaging.

“It was a beautiful exercise in engineering education and project management,” Buckley said. “This particular project with Melissa & Doug is a really great example of solving a meaningful problem for a company that everybody loves. The perception sometimes is that what you would do for a company like Melissa & Doug is always make a new product. Sometimes, yes, but there’s also some of what you’re seeing here, which is optimizing a really popular product with an eye toward cost and environmental sustainability or supply chain issues.”

While working with any team can be a challenge, navigating the problems of the project as well as differing personalities, Moore said the all-woman team — the first of such for this senior design course, according to Buckley — worked hard to have each other’s backs. And working with a female engineer from Melissa & Doug made the experience that much more empowering.

“We accomplished so much in this short timeframe,” Moore said. “We have six builds to display with a bunch of research to back it up, and a lot of testing that went into it, as well. We really had a lot of ‘pedal to the metal’ mentality.”

Tackling two designs to protect football players

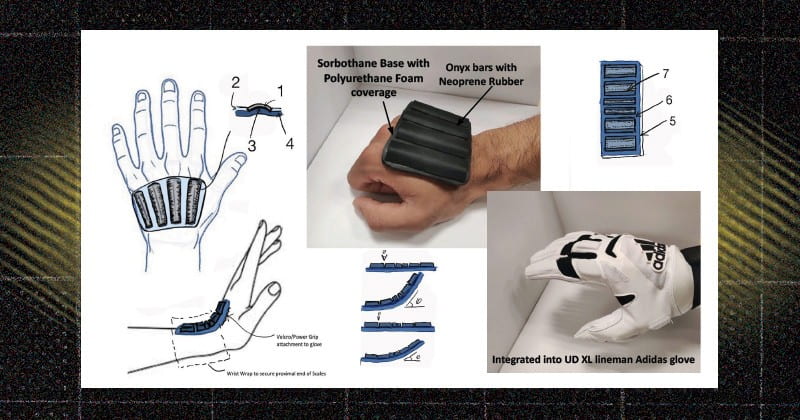

For their project with UD Athletics, mechanical engineering senior Raj Shah (Honors) and biomedical engineering seniors Emma FitzGibbon (Honors), Alyssa Giordani and Haonan “Switch” Huang created a prototype of a glove to protect the metacarpal bones of football players that have suffered a hand fracture.

Their prototype, which received the Rehabilitation Devices Award at the showcase, is a glove insert that has four carbon fiber bars and additional neoprene cushioning. The inserts can be customized to fit different glove sizes and provide lightweight, flexible protection for players during the long recovery process.

From left to right, Haonan “Switch” Huang, Emma FitzGibbon, Alyssa Giordani and Raj Shah created a prototype of a glove to protect the metacarpal bones of football players who have suffered a hand fracture. Their devices won the Rehabilitation Devices Award and the December showcase.

“The device they were using before was rigid and very player-specific, and we wanted to create a device that could be used more broadly with the ability to move and flex,” Giordani said. “We ended up combining two of our original brainstorm ideas to get this design, with individual coverage of each metacarpal but also different layers for comfort and protection.”

As a secondary challenge posed by UD Athletics, the team also created a device to help prevent wrist hyperextension when players hit the ground and land on their hands.

“When a player falls, the hand will be the first thing that touches the ground, and that will be the first thing that generates hyperflexion and is very dangerous for their wrist, so that’s where we came up with this device,” Huang said. Their resulting prototype can also be integrated with wrist taping to provide additional protection.

“We’ve gotten some really helpful feedback over the whole process from our sponsor, Brandon DeSantis, and also from our faculty adviser,” added FitzGibbon. “It’s fun to be able to go to the Whitney Athletic Center, talk to our consumers and be able to pitch our design and talk about it.”

Team 206’s prototype is a glove insert that has four carbon fiber bars and additional neoprene cushioning. The inserts can be customized to fit different glove sizes and provide a lightweight, flexible protection for football players.

Sonia Bansal, assistant professor in biomedical engineering, said that this highly motivated and effective team really hit the ground running with their project and took full advantage of having access to their clients. “Every tweak that they’ve made has been directly off of feedback, and they’ve been really nimble when it comes to eliciting and following through on that feedback,” she said.

The team, which plans to build off their existing designs based on continued feedback from their sponsor and the UD football team, said that while the process of finding the best materials and adhesives for their designs was challenging, the end result was incredibly rewarding.

“On top of getting to work with the football players, having a physical product — not just designing it on paper, but actually being able to hold something and putting it into a football glove — is super rewarding,” said Shah.

A crash course in problem solving

The team tackling Stanley Black & Decker’s plier-related project took home the Mechanical Engineering Chairperson’s Award (the highest award given during the Senior Design Showcase) and the Experiment/Education Tool Award at the December event.

Project lead Olivia “Vea” Hernandez and teammates Dominic Corona (Honors), Logan McKinney and Rory van der Steur were tasked with creating a text fixture that would apply and measure the force necessary for a pair of pliers to cut through various gauges of wire. Their end-product would ultimately be used in trade show settings by marketing professionals, as well as in labs by R&D engineers, so aesthetics and portability were driving factors in their design.

“The project is challenging, but has been an incredible opportunity to apply the cross-functional skills we’ve learned over the years,” Hernandez said.

But these mechanical engineers quickly realized they would have to incorporate coding and electronics that could read and display data, while also working heavily in the mechanical engineering department’s Student Machine Shop. Not only that, but they also had to deal with the real-world challenges of a disrupted supply chain, which included handling budgets for rapid shipping of custom parts and consistent communication with vendors.

Working on a project sponsored by Stanley Black & Decker, a team of seniors were tasked with creating a text figure that would apply and measure the force necessary for a pair of pliers to cut through various gauges of wire.

Throughout the fall semester, Hernandez said she and her teammates were in the Machine Shop nearly every day customizing parts for the project — a lot of “rapid prototyping,” as she described.

“That’s what engineering is about: problem solving, and we’re getting our fill of that,” she said, adding that the team is optimistic that their project will be useful to their corporate sponsor.

“The Senior Design experience in general — and this team is a particularly good example of it — is about integrating everything these students have done over the course of their time here at UD,” said Alexander De Rosa, the team’s faculty adviser and an associate professor in mechanical engineering. “As students, they’re more like consultants working for these companies.”

He said these projects not only give students new engineering experiences, but also help them develop more practical skills such as communication, presentation and other soft skills, all on a very rapid timeframe of one single semester.

“They’re not only dealing with these logistics, but also have to learn some new things as well,” he said. “The hope is that all our students become self-directed learners who not only master subject material, but also develop self-awareness to know where some of their blind spots are.”

A modular approach to empowering kids

Biomedical engineering seniors Michael Trainor, Brendan Cohen (Honors), Nicholas Wickersham and Suzannah Hoguet (Honors) and mechanical engineering senior Gavin McMahon were tasked with prototyping a device for children who were born missing part of their arm that would enable them to ride a bicycle safely and independently.

“With a lot of the options on the market, you have to buy a whole custom bike or use costly medical prosthetics that need to be specially fit or molded and are not really easily replaceable,” Hoguet said.

From left to right, Gavin McMahon, Nicholas Wickersham, Suzannah Hoguet, Brendan Cohen and Michael Trainor with their adaptable bicycle prototype at the December showcase.

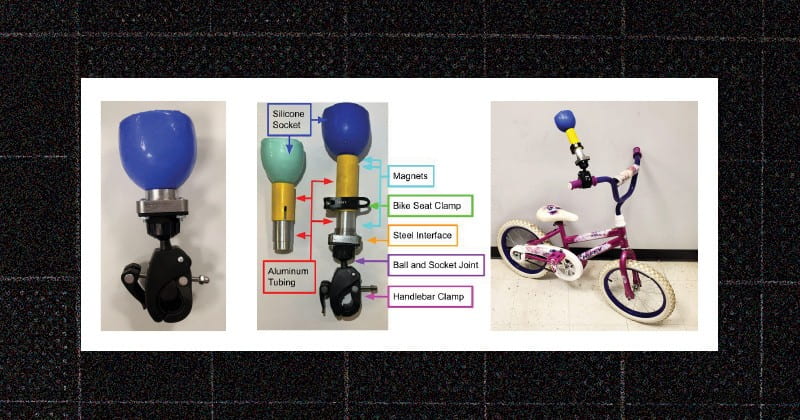

After evaluating the currently available devices, the team came up with a list of “constraints and wants” and from there worked on brainstorming specific designs. Taking into account safety, cost, ease of use, the ability to work for different ages and limb lengths, and staying in close contact with their project sponsor Dr. Jennifer Ty, at Nemours Children’s Health, the team’s final design is an adjustable post that attaches to a handlebar along with a cup and joint structure that detaches in case of a fall.

“One huge difference with our design, and something that is creative compared to anything else in the market, is the one-size-fits-all aspect,” said Cohen. “This is also a really safe option, and a big reason for that is that there are several breakaway components in our design.”

Bansal was the adviser of this and several other of this year’s capstone projects.

“These students have done a really great job thinking about this modularly so it could be adaptable for other conditions,” Bansal said. “In addition, they were really focused on how we make this as inexpensive and as replaceable as possible while thinking about their work in a socially conscious and responsible way.”

In a project sponsored by Nemours, students developed an adaptable device to help children with a congenital below-elbow amputation use a bicycle independently. Team 202’s final design is an adjustable post that attaches to a bike handlebar, along with a cup and joint structure that detaches in case of a fall.

In the process of creating their adaptable bicycle prototype, which they hope to continue refining and improving this spring, the team said that they learned a lot about the process of design and enjoyed having the freedom to pursue different ideas.

“It was also nice to hear that our project might be able to be used in the future,” Wickersham said. “Whether that be a future senior design team, or we hand it off to Dr. Ty and she does her own testing, either way it will be cool to see the end result if it moves forward.”

Article by Maddy Lauria and Erica K. Brockmeier | Photos by Kathy F. Atkinson | Illustrations by Joy Smoker | February 07, 2023